A series dedicated to literature in translation whether classic or contemporary.

Originally published in 1945 as Na Drini Ĉuprija

Translated from the Serbo-Croat by Lovett F. Edwards

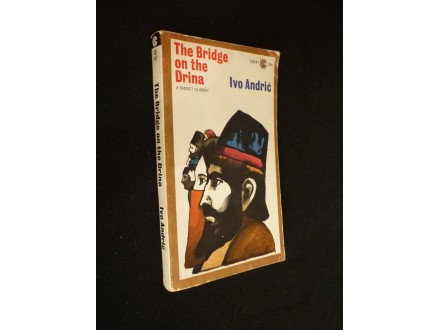

A Signet Classic from 1967

Yugoslavian literature, much like the nation forged in the aftermath of the First World War, stands unique in the field of European literature. The Bridge on the Drina, by Ivo Adrić, the 1961 Nobel Prize-winner, functions as an experiment in literary modernism and as a kind of ur-text for Yugoslavian literature itself. Encompassing four centuries in a chronicle of daily life and political upheaval, Drina follows the lives of the villages of Višegrad from 1571, when the bridge was constructed, to 1914, when it was destroyed.

The novel, despite its small size – my Signet Classic is a 334-page pocket paperback (minus the Translator’s Foreword and the Afterword by John Simon) – contains a cavalcade of miniature portraits and literary styles. It begins in the mode of a creation myth, telling of legendary figures and tall tales told and retold by the villagers of Višegrad. By the end, the novel has ensconced itself into a more realistic mode, replete with individual struggles against economic and sociopolitical forces, reminiscent of French writers like Balzac and Zola. Yet the transitions from medieval to early modern to modern societies come across as seamless.

Andrić paints these portraits and the changing times with an atmospheric brush, mannered and ornate, yet not distracting or self-consciously “clever” in its execution. In the opening chapters, he tells the story of a little boy who would grow up to the Sultan’s Vizier. Looking back on the town, the boy, taken as tribute and later to be raised as a Janissary, the author recreates the boy’s mental state:

“He surely forgot too the crossing of the Drina at Višegrad, the bare banks on which travellers shivered with cold and uncertainty, the slow and worm-eaten ferry, the strange ferryman, and the hungry ravens above the troubled waters. But that feeling of discomfort which had remained in him had never completely disappeared. On the other hand, with years and with age it appeared more and more often; always the same black pain which cut into the breast with that special well-known childhood pang which was clearly distinguishable from all the ills and pains that life later brought to him. With closed eyes, the Vezir would wait until that black knife-like pang passed and the pain diminished.”

The novel explores the tense coexistence of the Bosnian and Turkish communities. The brutal rule of the Ottoman Turk is contrasted to the bureaucratic petty tyrannies of the empire of Austria-Hungary. In both cases, Višegrad exists in a liminal space, as a kind of outlier of both empires. But geopolitics and the processes of imperial rule remain distant and abstract. Only in rare cases do the tendrils of political power impinge on the community and the bridge. Mostly it is everyday life. Weddings and funerals, trade to and fro across the bridge, and idle hours spent on the bridge’s kapia. (While the characters and manners may seem exotic to an American reader, the kapia’s social scene could be seen as akin to Sam’s bar on Cheers.)

In what would otherwise be a momentous occasion, the handoff of Višegrad from Ottoman to Austrian rule is handled with a serio-comic anticlimax. Several chapters beforehand, the villages speak in hushed voices about rebellions and insurgencies against Ottoman rule. Each successive rebellion and its attendant quashing seem like a desperate attempt to push back a powerful and inevitable wave. But in the end, the Ottomans leave and the Austrians arrive with minor ceremony and a proclamation nailed to the bridge.

Drina mirrors Yugoslavia’s idiosyncratic political position in the Cold War hegemony. Created in the aftermath of the First World War and stitching together various ethnic groups (Bosnians, Serbs, Croats, etc.) and different religious communities (Christian and Muslim), it shook off the shackles of Nazi Occupation by embracing Communist rule. But Yugoslavia had been under Ottoman and Austrian rule for centuries, always a pawn in some imperial chess game. Yugoslavia under the dictator Joseph Tito sided with the Soviets but didn’t become a “satellite state.” It was Communist but wasn’t a member of the Warsaw Pact, instead becoming part of the Non-Aligned Movement. Drina reveals not necessarily the political background, although Ottoman and Austrian tyrannies are exposed for what they were, law and order wrapped up in false promises and cheap rhetoric. It also serves as a prophecy for the fragmentation and violence that will follow the dissolution of the Iron Curtain.

After the assassination of Archduke Francis Ferdinand by a Bosnian nationalist, the mood turns ugly and Austrian rule sloughs off its hypocritical benevolence, since the Hapsburg officer corps remained a German-speaking body, its ethnic chauvinism camouflaged in military pomp and ceremony. Andrič’s novel, told in a masterful and modernist interpretation of the national epic, reveals the trials and tribulations of Višegrad’s people, with the bridge as the central unifying symbol, seeing the various ethnic and religious communities with a humanizing eye for detail. In these days of political division, an increasing normalization of political violence, and the relentless doublespeak of political campaigns, Drina shows how centuries of tense co-existence can reveal itself in the hearts and minds of individual villagers. The bridge is shown as universal and eternal … until it isn’t, blown apart by retreating troops of an ossified decadent empire.