Small-sized reviews, raves, and recommendations.

Hannibal Lecter: First principles, Clarice. Simplicity. Read Marcus Aurelius. Of each particular thing ask: what is it in itself? What is its nature? What does he do, this man you seek?

Clarice Starling: He kills women…

Hannibal Lecter: No. That is incidental. What is the first and principal thing he does? What needs does he serve by killing?

Clarice Starling: Anger, um, social acceptance, and, huh, sexual frustrations, sir…

Hannibal Lecter: No! He covets. That is his nature. And how do we begin to covet, Clarice? Do we seek out things to covet? Make an effort to answer now.

Clarice Starling: No. We just…

Hannibal Lecter: No. We begin by coveting what we see every day. Don’t you feel eyes moving over your body, Clarice? And don’t your eyes seek out the things you want?

Silence of the Lambs (Jonathan Demme, 1991)

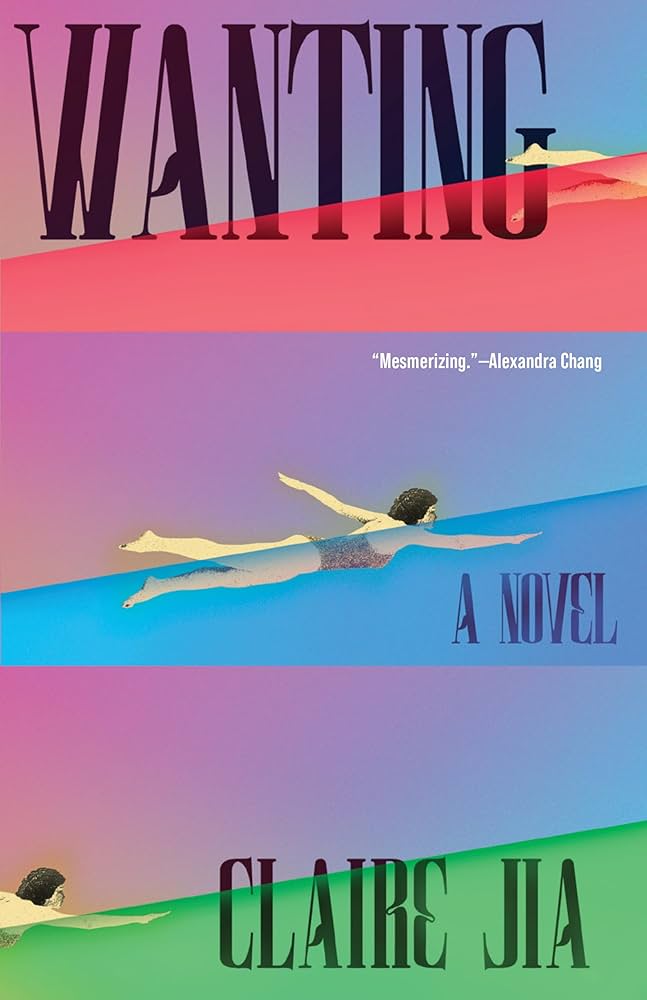

Wanting by Claire Jia is an epic tale of friendship, betrayal, adultery, media, and resentment. At the center are two friends. Ye Lian, a strait-laced educator living in Beijing. When her childhood friend, Luo Wenyu returns to China with a millionaire fiancee in tow, Lian seethes with resentment. Since she was young, Lian has wanted to live in America. Wenyu has fulfilled that dream, earning a living as a YouTube influencer. In the process, Wenyu has hired Song Chen to build her dream house. Bubbling beneath the surface of public posturing and expected social behaviors is the dark undercurrent of desire. Wanting is a group portrait of modern China in all its socioeconomic contradictions. To paraphrase what a character says, “China is where every communist thinks they deserve to be a millionaire.”

Ye Lian behaves as the “good girl,” working a well-paying job teaching the children of the privileged classes English. Training them to enter (preferably) American colleges. Despite her obedient outer appearance, Lian resents her students and their assumed advantages. Since she was a child, she has always wanted to live in America. Much later in the novel, she visits America as a tourist, but she would find the experience shallow and superficial. Like many, she desires to see the “real America.”

Cracks start to emerge in the novel, sending fractures what would otherwise seem to an ordinary narrative about otherwise ordinary people. We learn early on that as children Ye Lian and Luo Wenyu would conspire to shoplift from local convenience stores. When Lian and Wenyu reunite at the latter’s engagement party, her impending marriage would become threatened by the re-emergence of a high school crush, a former bad boy. Lian’s teaching career would provide an opportunity for a kinda sorta adulterous liaison with a student. When the harmless infatuation evolves into an arranged meetup in real life, the adultery becomes less of a theoretical exercise and more real. Where does one draw the line? When does it become a case of actual adultery?

A third element enters the novel when we read about the life of Song Chen, an older architect. What Claire Jia does so well could be classified as “reverse revelation.” Or more crudely as a kind of narrative bait and switch. In the present, Song Chen is dealing with the bureaucratic nightmare of constructing Luo Wenyu’s dream house. At home he deals with a crumbling marriage and in his work life negotiating with the local Party boss. (While not an actual Party member, the “boss” is a local government functionary. He knows whose palms to press and how to get things approved in a diligent fashion.) As with most architectural endeavors, behind the brilliant designs involve the less glamorous work of permits and approvals.

Song Chen’s climb to the top as an architect involved time working as a bus boy in a Chinese restaurant. Jia’s paints a portrait of his personal resentment on a visceral level. His personal failures and humiliations, the agony of having to endure this menial job, and his inability to communicate to his wife his situation. It all feels justified. In the present-day United States where we see once again the hydra-headed monstrosity of white backlash, it is instructive to see where these underground rivers of anger and rage come from. Resentment isn’t created in a vacuum. It comes from somewhere. Whether or not those affected are actually justified in their feelings is tangential, since those feelings still exist and fingers need to point at someone or something. Resentment is fueled by blame. Song Chen’s resentment feels completely justified until it isn’t. Jia’s slow-burn is masterful in execution, especially as it reflects off Ye Lian’s resentment of Luo Wenyu’s luxurious lifestyle.

The novel unfolds in grand style, reminiscent of the best of Honoré de Balzac. Wanting is Balzackian, as opposed to Dickensian. Wanting is a panorama of appetites and passions. Desire becomes something that threatens to burst out of control, a chaotic shattering of social norms and behaviors. Yet, at the same time, desire is the prime engine fueling global capitalism. We desire the thing and we want to get the thing. Desire also drives personal ambition, whether for fame or attention or acceptance. Desire will make us humiliate ourselves in order to achieve some goal. (Even if the goal will be found to be impossible or illegal or not worth the effort.) Despite the superficial notion that China is a well-behaved Communist utopia, the very human need of wanting something cannot be crushed by any ideological force. We may apply the mask of civility and decorum, but beneath we all want something. We covet. No political force or biblical commandment can prevent that.