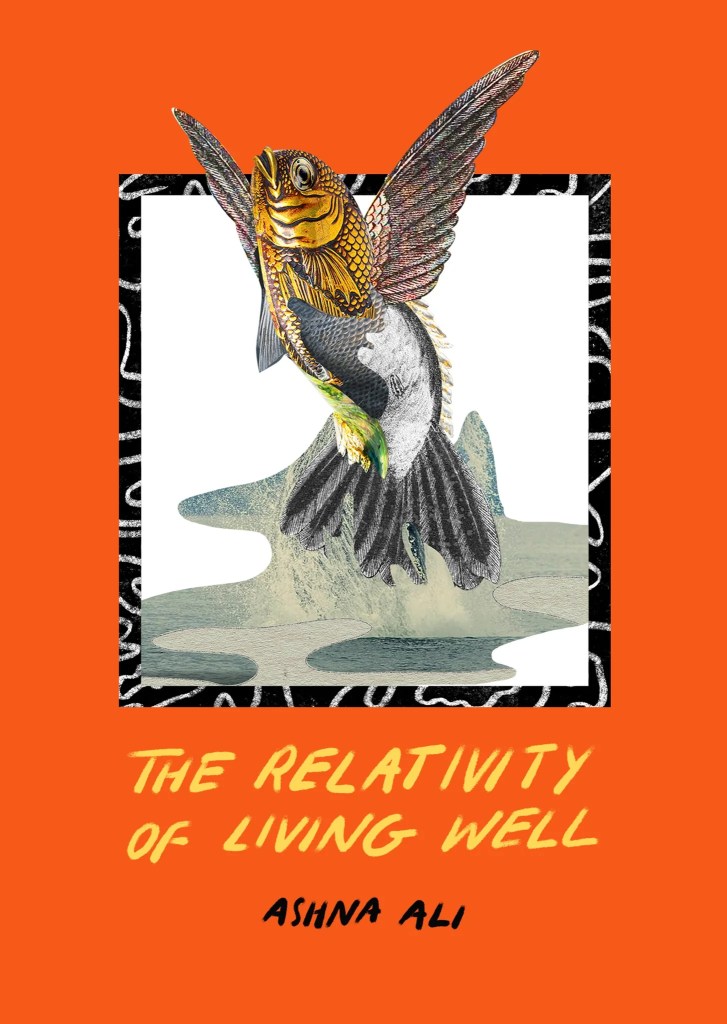

The Relativity of Living Well, by Ashna Ali

Bone Bouquet (2024)

Hardly Creatures, by Rob Macaisa Colgate

Tin House (2025)

Reading debut works is always a lot of fun. Devoid of preconceptions and the weight of literary legacy, these works can be encountered with a clear eye and an open mind. These two volumes of poetry are debut collections by LGBT poets of color living with disability. That’s a lot to unpack. To use another literary term, it seems “overdetermined.” Yet this is a predictable response to an individual with multiple conditions.

Ashna Ali’s The Relativity of Living Well debuted in 2024 from the deliciously named small press Bone Bouquet. Ali (she/they) “is a queer and disabled child of the Bangladeshi diaspora raised in Italy and based in Brooklyn, NY.” Hardly Creatures, by Rob Macaisa Colgate, is forthcoming in May 2025, published by Tin House (distributed by W.W. Norton). Colgate is a “disabled, bakla, Filipino American poet from Evanston, Illinois.” Bakla is a Tagalog term for one who is AMAB (assigned male at birth) but whose gender expression is feminine. It also has a religious/spiritual component akin to two-spirit and hijra. (While these cultural parallels shouldn’t be considered exact, it is noted for the purposes contextualization and familiarity.) Again, these descriptions are taken from the biographies on the back covers, and a cis-het white male is writing these reviews. Any additional information, corrections, critiques, expansions, etc., are welcome. Write them in the comments section and we can expand this conversation. Due to the fluidities inherent within intersectionality, one shouldn’t be under the impression that these reviews are somehow the last word. The opinions expressed are mine, but they are one among many.

The reviews here are subjective, immediate, and taste-based. Taste can be irrational, personal, and borderline non-sensical. It’s when morality and/or ideology gets tangled up in the machinery of personal taste that things can become complicate and problematic. At the same time, one shouldn’t file down the spikes and horns of personal taste in the desperate appeal for some bland mediocre middle-ground. In these latter-days of the Internet one shouldn’t be too fearful of offending someone or pissing off someone. Someone will always be offended or pissed off by something. The Internet can become a swirling black hole of misplaced inarticulate anger and resentment. We have become addicted to manufactured crisis and having social media whip us into a frenzy. Don’t get riled up and angry, only to be manipulated into having some corporate behemoth profit from your doomscrolling and clicks. That’s a primrose path to poisoned mental health. Maybe lay off the social media for a bit?

That lengthy digression aside: The Relativity of Living Well, by Ashna Ali, is an angry and tender poetic screed written in the dark shadow of the COVID-19 pandemic in New York City. As people’s conception of time blurred and sheltering in place drove us stir-crazy, Ali writes a chronicle from the belly of the beast. But amid the slow-motion atrocity exhibition of the waning days of Trump’s first presidency, Ali describes moments of togetherness and resilience. They unite with “disabled kin and kindred.” After all, the queer community has weathered a pandemic before with the AIDS crisis. (Another time a Republican administration sat on its hands and did nothing.)

Ruthie reminds us, abolition is presence.

I’m talking about being here in the full flesh

of your body in all of its brokenness

and beautiful mess.

We gather around the Zoom room

to discuss. (“Social Distance Theory”)

Disability can mean both erasure and exposure … or with Donald Trump, obscene mockery. Yet there is real push-back. One’s body can be a broken and beautiful mess, but it can be beautiful because it is a broken mess. Think of the fragile beauty of Blance DuBois, beautiful in its fractured damaged state.

Pain days undulate time. I become

only a slackening. Unwashed dishes, hands,

character. I understand, but you have

a professional responsibility. (“Who Is Responsible For Your Mercy?”)

Ali deals with chronic pain and its impacts on their personal life. Their body becomes a site of poetic expression. At the danger of epic understatement, it creates inconvenience. But it is not all negativity, since Ali speaks of the “queer, crip” community banding together for collaboration and creativity. The forces of old and evil want to do everything to erase this unique community/ies, but they refuse to let that happen. For all the litanies and inventories of criminality, racism, and hypocrisy, The Relativity of Living Well is a celebratory work. Perhaps the greatest “Fuck you!” one can give to a bigot is by stating the obvious: “I’m here. I exist.” These poems reveal a poet faced with multiple overlapping discriminatory practices and reveals a voice filled with love, rage, and intelligence.

These poems establish a new voice in American poetry. It is a work that reveals the challenges of a particular set of circumstance (queer, POC, disabled) yet can have value for anyone that reads it regardless of personal background.