Small-sized reviews, raves, and recommendations.

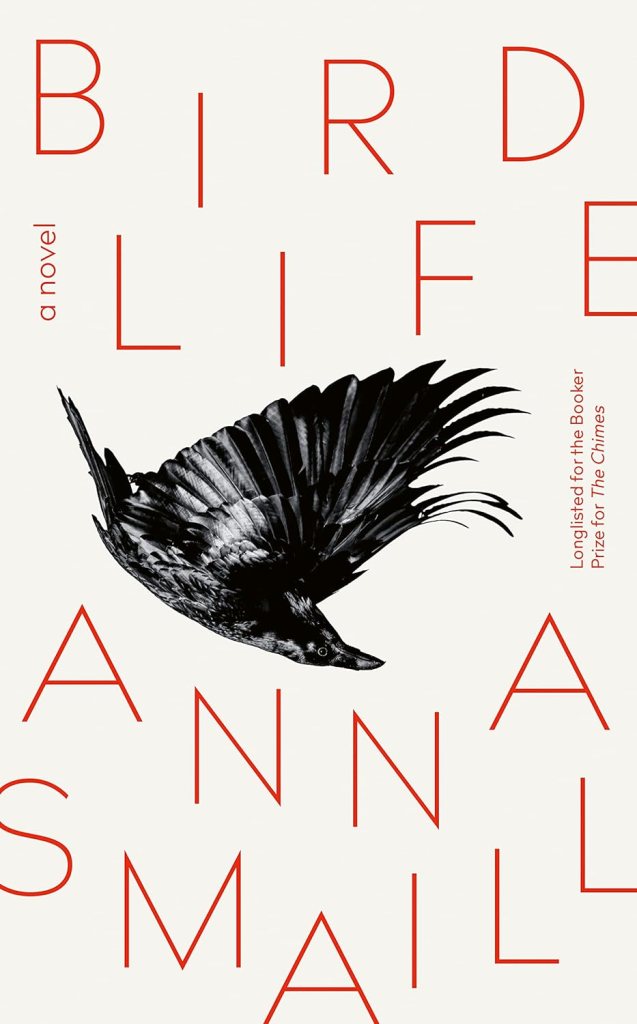

Tracing the interconnected lives of two women in contemporary Japan, Bird Life, by Anna Smaill, explores the porous boundaries between genius and madness, trauma and genius. Smaill, who wrote the Booker Prize longlisted The Chimes, a dystopian tale about the abolition of memory, further investigates the scars of memory and the after-effects of personal trauma. Bird Life focuses on two women, both teachers at a Tokyo university. Dinah, an expat from New Zealand, teaches in the English-language section. Yasuko also teaches at the university. Dinah’s brother, Michael, was once a gifted concert pianist destined for fame and glory, until he wasn’t. Yasuko has a close relationship with her only child, Jun. One day, without warning or notice, Jun disappears.

We follow Dinah and Yasuko in alternating chapters until they finally, inevitably, meet. Dinah lives in an eerily deserted apartment block in central Tokyo, a fact even her English-speaking colleagues at the university refuse to believe. Yasuko, we learn, has had the gift of speaking to animals. When her son is born, the gift disappears. When Jun disappears, she tries hard to recover the gift, in a desperate attempt to use it to find the whereabouts of Jun.

Bird Life blurs the line between the visionary and the mad. Dinah and Michael led a charmed childhood until his piano lessons separated them. Their intimate childhood, coupled with their active imaginations, make the pair similar to Brenda and Billy Chenoweth from Six Feet Under. (Smaill’s novel of loss and recovery recall the short stories of Mary Kennedy Eastham.) With each successive chapter, the layers of exterior normalcy of the siblings slowly peel away. Is the status of being mentally abnormal a socially-imposed condition, a kind of Pavlovian conditioning, or is it a sign of a serious mental health issue? In the case of Yasuko, the only child of a university scientist, her gift becomes more of a curse. Her parents aren’t amused by such antics. It flies in the face of scientific rationality. Yasuko also cultivates a sophisticated outer carapace as a shield against the world’s traumas. Her attitude is aloof, condescending, almost misandrist in her relations with the men at the university. But as the novel unfolds, these outward postures of defiance and haute couture become better explained, if not necessarily justified.

While this might appear like yet another novel that might wallow in mawkish sentimentality or indie movie miserablism, it is neither. Bird Life couples together, with studious brilliance, a deft use of conventional narrative devices (set-up, callback, payoff) and gorgeous polished prose. Smaill is adept at dropping a bon mot amid wonderfully atmospheric passages. When explaining Yasuko’s childhood: “It was only right that the two worlds should be separated, because her mother’s was plain and uncomfortable while her father’s was one of magic and transformation. He was a crystallographer. A scientist of snow. Under the microscope the small fragments of crystal revealed their structures they leapt up and scattered.”

Bird Life, by Anna Smaill, is another addition to Scribe’s collection of “Pacific Rim literature” (the place, not the movie). New Zealand and Japan, despite being separated by many miles, encompass two facets of the Pacific Rim’s various cultures and nations. The novel’s exploration of genius, madness, trauma, and recovery make it highly relevant today, especially with the concern for mental health, self-care, and the burden artistic genius can carry on those not ready for its demands.