Small-sized reviews, raves, and recommendations.

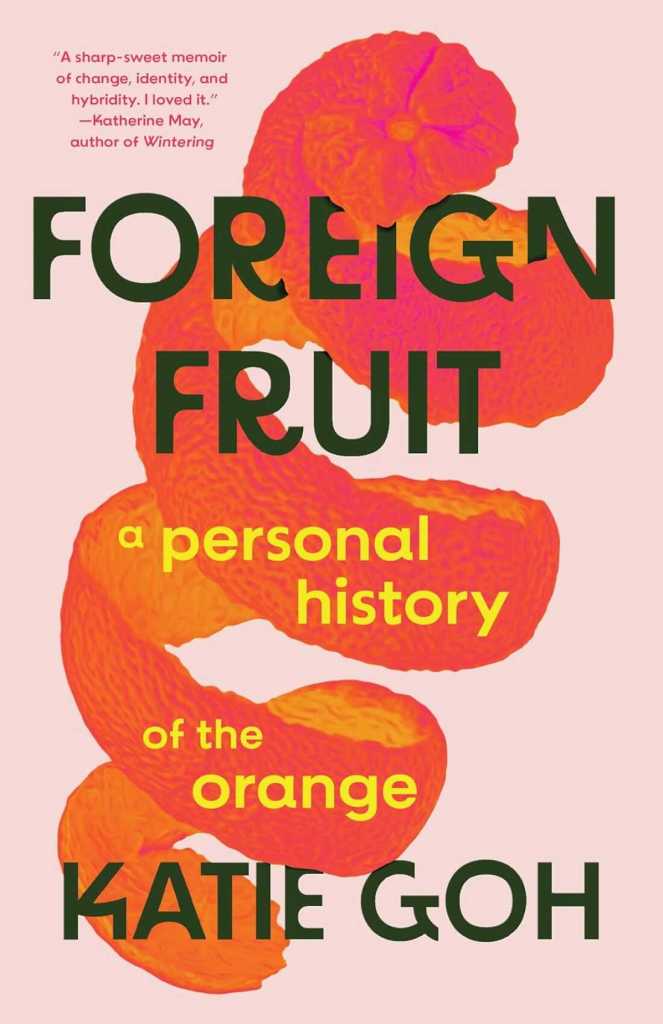

“The morning after a white man murdered six Asian women, I ate five oranges.” Simultaneously horrific and mundane, this is the first sentence of Katie Goh’s memoir, Foreign Fruit: A Personal History of the Orange. Throughout her global journey, this sentence returns. A lightning bolt. A gut punch. A simple statement of utter obscene singularity, it becomes the thesis of her entire project. Koh, a queer writer of mixed ethic heritage living in Northern Ireland, explores the history of the orange. An otherwise simple household object, the orange becomes a symbol of hybridity. As Koh states the book is “about the orange intersecting with empire, colonialism, migration, and globalization throughout its history.” In her search to uncover the orange’s history, she travels to Holland, Vienna, Los Angeles, and Kuala Lampur.

Koh’s writes with a seamless blend of the personal and the historical, equal parts memoir and essay. It reflects a multifaceted hybridity, since this book fails to be either wholly subjective or objective in its coverage of the subject matter. Koh and the humble orange also possess a hidden hybridity. She relates growing up about feeling out of place, both as a gay woman and as an Asian growing up in Northern Ireland. At times she felt the need to pass for white. And, coincidentally enough, Northern Ireland has the Orangemen, self-anointed representatives of British Protestant colonial tyranny. (Ireland, until the 20th century and war and partition, England’s closest and oldest colonial possession.)

And who are these Orangemen, Koh explains: “A Unionist, Protestant stronghold in the northeast of Ireland, our town was the living legacy of centuries of British colonial occupation. Here, religion was wielded in the community with an iron fist. In July, Orangemen – named for the Protestant King William, not the orange – marched under red, white, and blue bunting, and on the month’s eleventh night, effigies of Sinn Féin politicians, racist placards, and Irish flags hung from bonfires. After the bank holiday, the politicians who’d joined in with these festivities returned to Stormont to ensure abortion access and same-sex marriage remained criminalised.”

During her global journey, she uncovers many things. These include three different origin stories of the orange based on the life of Brother Marie-Clément Rodier, a history of the Dutch East India Company, and an anti-Asian race riot in 1871 Los Angeles. And for those looking for an economics of global salvation, she recounts the citrus-related famine of Mao’s Great Leap Forward and the capitalist famine of the Great Depression as illustrated in Steinbeck’s Grapes of Wrath. Farmers had to destroy excess crops in order to avoid prices cratering and communists ended being as corrupt and inept as the capitalist running dogs they passionately criticized. Yeah, both systems suck.

On her trip to Southern California, her critique of American culture becomes acidic, although not inaccurate. “I had come to California to find orange trees, and I had also found enough for a lifetime. But in the groves, I had also found the self-mythology of a citrus industry in a nation which grew from roots of supremacy, exclusion, and destiny. The fruit it offered dangled like fool’s gold: beautiful and tempting, empty and worthless.” What could have come across as yet another scolding from some Gen-Z Leftist Killjoy has become a verbal barb worthy of the pen of Karl Kraus or Evelyn Waugh. (Waugh, despite being a British conservative Anglo-Catholic, wasn’t keen on America’s empty materialism and spiritual vacuousness.)

Koh has written an engaging personal history of a mundane supermarket staple. It is a riveting and enriching read, a seamless mix of her own hybrid history and the torturous, sometimes painful, history of a bright orange fruit. Like sugar, coffee, and other staples we take for granted, it is a history drenched in blood, colonialism, and oppression. Yet Foreign Fruit is not all doom and gloom, Koh shares positive experiences with her family, at home and abroad, and uncovers the richness encased beneath an orange skin.