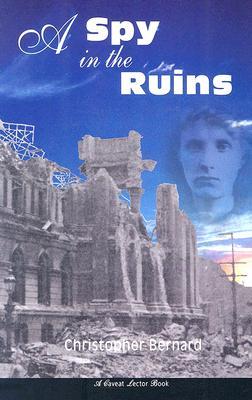

Described by Anna Sears as “A Bildungsroman hallucinogenic in its intensity,” A Spy in the Ruins by Christopher Bernard constructs a postapocalyptic anti-narrative replete with verbal richness, political aggression, and erotic tenderness. The back cover blurb by Jack Foley asserts Spy “is a book not for the faint of criticism.” A book this intense, word-drunk, and ferocious demands a proper dissection and investigation.

Spy is an idiosyncratic book about the Sixties and the moral consequences. At the same time, it encompasses much more in formal experimentalism and in vicious verbal assaults. The only other fiction where one encounters lacerating indictments “our vexed, complicated, technomiserable situation” (again, Jack Foley) are in the works of Louis-Ferdinand Céline, Alexander Theroux, and Thomas Bernhard. Despite the formalistic challenges presented in the text, an almost physical immediacy haunts the text.

While the current trend in literary circles is to bow before the Cult of the Sentence, crafting polished gems befitting the pages of the New Yorker, Bernard rips apart and defiles the sentence. It takes a while to adjust to the flow of the novel. Bernard creates scenes with run-on unpunctuated sentences followed by. Brief. Breaks. In the text. This is off-putting at first, but eventually this becomes a means to instill a specific tone for the novel. With the breaks and the run-ons, Bernard’s style balances between that of a prose poem and an epigram.

The plot of the novel follows the life story of “the solitary one,” an unnamed (for the most part) male whose formative experiences include some political activism in the Sixties. Divided into ten chapters with an overarching framing device, Spy follows the Solitary One from birth to death. Besides the narrative style, the first half of the novel is notable for its insistent vagueness. There are discrete scenes and characters, but lacking in proper names and location. It creates a mythic, dream-like quality, apropos since Foley (again) compares Spy to Finnegans Wake. (In his blurb, Foley likens Spy to both Ulysses and Finnegans Wake, a comparison the novel almost achieves.)

The only time the novel really fails to deliver is in passages obviously set in the Sixties but seemingly clouded in a willful vagueness. The Kennedy assassination is described as a leader killed in a Southern city. It is only when the accretion of historical facts lean against the mythic edifice of the novel that things begin to strain.

The Solitary One endures a brutal upbringing, only leavened by his nascent sexual experiences with a female schoolmate. But his upbringing drain these erotic scenes of their joy and later corrode and curdle in his later relationships. The last sections involve him enduring a one-way conversation with his former lover. The scene possesses a vicious mood with the Solitary One desperately wanting to answer, but prevented by his deteriorating health.

Prior to that, Spy has chapters increasing in specificity. A screenplay has a Him and Her where we see a relationship fracture amidst the earnest political discussions one witnesses in bright-eyed college students. The ninth chapter begins as an espionage novel and ends as a Therouvian indictment of modern culture’s shallowness and rot. Characters get specific names, but we are unsure whether this is a realistic depiction or whether the hospitalized Solitary One is making this up in his head, retconning the past to make his mistakes more palatable. The chapter is less Tinker Tailor Soldier Spy than Malone Dies.

Bernard marries the formal experimentalism of James Joyce with the unflinching emotional brutality of Samuel Beckett. Written in 2005, A Spy in the Ruins has a bold experimentalism welded to a strident and intelligent point of view. It stands toe-to-toe with Infinite Jest, Angels in America, and The Savage Detectives as an epic that has a lot to say and does so in a new invigorating way.

Agree. The few who’ve read A Spy in the Ruins have to be impressed. Bernard has written a modernist masterpiece in a post-postmodern world, and that makes it unique in its echoing way. I think this book will find its way to future generations, many many years hence.

LikeLike