The Benefits of Hindsight

Politics is the art of looking for trouble, finding it everywhere, diagnosing it incorrectly, and applying the wrong remedies.

Groucho Marx

Henry Kissinger wrote his final volume of memoirs, Years of Renewal, in 1999, at the cusp of the new millennium and in the final years of the Clinton Administration. Why did he wait nearly two decades to publish this volume? White House Years came out in 1979 amidst the foreign policy disasters of President Jimmy Carter. The book’s tone, coupled with its colossal size, exudes an Ivy League public intellectual’s not-so-veiled justification for his service in the Nixon Administration and its foreign policy successes. It is a classic example of using the genre of the political memoir to explain why Kissinger was on the right side of history. In the late Seventies, with the Gas Crisis, the Hostage Crisis, and an earnest, honest, utterly inept Georgia peanut farmer in the Oval Office, it seemed Kissinger made a compelling case.

The second volume, Years of Upheaval, arrived in 1981, ready for the bookshelves of Reagan Revolution apparatchiks. With the Gipper residing at 1600 Pennsylvania Avenue playing the greatest role of his career (not counting the movie he did with the chimp), America was ready for a change, including deregulating the banking industry and a little missiles-for-hostages do-se-do. The Nixon Crew was never well liked among the Movement Republicans, with Watergate as the Five O’clock Shadow of Executive Privilege Run Amok. Richard Nixon, the Grand Poobah of Red-baiters, poor Quaker son from Whittier, California, entered the White House on a strong platform of Law and Order, ended up dragging nearly his entire administration to the slammer in a political apocalypse of criminality, corruption, and paranoia. Kissinger gives an insider view of the slow-motion train wreck of Watergate and how the Nixon White House under siege undermined its foreign policy goals. The best bits are the conversations with the various dictators, despots, and deranged authoritarians, all comforting Henry K. by saying, “In our country, Watergate would never happen.” They should know, since they have the disappearances, mass graves, and Black Marias to prove it. But hey, at least those murderous psychopaths with absolute power weren’t Communists.

The first and second volumes each topped out with at one thousand pages (White House Years is a ludicrous 1400 pages long). Years of Renewal, by contrast, has only 1079 pages (not counting the Notes and Index). Besides the short length, Kissinger spends ninety pages summarizing Nixon’s foreign policy legacy, Nixon’s personal background, and justifying the crimes of Watergate. By all accounts, Years of Renewal comes off as rather slight.

“Our long national nightmare is over.”

“Our long national nightmare is over.”

Kissinger’s final volume recounts his years in the Ford Administration and the array of foreign policy challenges ranging from apartheid to ethnic wars and even a little piracy. The post-Nixon White House is a chronicle of a foredoomed presidency, the end of shuttle diplomacy in the Middle East, the unraveling of détente, and the rise of the neoconservatives in the Republican Party. Kissinger regales the reader with his trademark style, an admixture of academic pedantry, sly wit, and diplomatic genius.

Shuttle Diplomacy, the End of Détente, and Arab Spring

Alliance, n. In international politics, the union of two thieves who have their hands so deeply in each other’s pocket that they cannot separately plunder a third.

The Devil’s Dictionary, Ambrose Bierce

After the smoke from Watergate dissipated, Henry Kissinger found himself the only survivor of the previous administration. The constitutional crisis created something unique within the annals of foreign policy and executive power. Kissinger became a de facto “foreign policy president,” with his dual role as National Security Advisor and Secretary of State and institutional symbol of continuity and stability during the rocky transition period. Besides negotiating the end of the Vietnam War, the other major area Kissinger lent his considerable diplomatic skill was the Middle East, still a tinderbox after the Six Day War.

While Kissinger goes into minute detail of the difficult negotiations, the geopolitical aftermath of the Six Day War provided an opportunity for the Administration. With Nixon out of the picture and Congress temporarily assuaged with his resignation, the re-stabilized domestic sphere gave Kissinger a better chance at negotiation with the various belligerents. But it wasn’t all wine and roses for the globe-trotting Secretary of State, since Congress sought to cut the purse strings on any new-fangled military adventure the Executive Branch might use as a bargaining tool. The post-Watergate Congressional elections also brought in a massive influx of anti-Nixon Democrats, or in Kissinger’s words, “McGovernite peaceniks”. This made Kissinger’s job more than a little difficult, since he the stick of American military intervention would be unavailable.

The situation became even more complicated with the Rabat Decision, when the Arab nations agreed to defend Palestine’s right for self-determination. The irony was all the knots into which the United States tied itself during the Peace Process. Kissinger, acting on behalf of the White House, engaged in personal talks with the various Middle East leaders, working tirelessly to end the belligerency in an effort to get both sides together to sit down and talk to each other. In the process of this goal, Kissinger helped forge numerous new alliances with the Middle East powers. While the despotism remained, the various leaderships switched their alliances from the Soviet Union to the United States. Unfortunately, the pro-US stance did not alleviate the anti-Israeli sentiment. Their championing the Palestinian cause added new layers of irony and difficulty. Since the Middle East isn’t really a place for compromise and sensibility, both sides asserted the right to exist alongside a theological desire to annihilate the other side.

Amidst the negotiations, the foreign policy of détente began to crumble. The changing international situation merited a reassessment of foreign policy goals, further exacerbated by the rise of Republican neoconservatism. For decades, the Cold War’s diplomacy fit under two interrelated concepts: brinksmanship and containment. The first was a matter of strong defense and the nerve of a duelist, the United States going toe to toe with its adversary, the Soviet Union. The Berlin Airlift and the Cuban Missile Crisis are examples in popular folklore of brinksmanship. (In reality, the Cuban Missile Crisis involved long-term negotiations and trading missile bases for accepted security guarantees. The book, When President’s Lie, by Eric Alterman, describes the situation in much more detail.) Containment involved the United States using diplomatic, economic, and military measures to contain the expansionist aggression of the Soviet Union. It involved sending troops to such places like South Korea, West Germany, and South Vietnam.

By the mid-Seventies, the American people and Congress were getting sick of bankrolling “containment,” least of all when it didn’t work. Détente was the Nixon White House’s brilliant idea for ending the Vietnam War. It involved Kissinger negotiating with the Soviet Union and China, the former the economic and military patron of North Vietnam. The Middle East, long a bastion of Soviet support, was the other puzzle piece. Included in détente was the associated issue of nuclear annihilation. Anti-nuke protesters and the Nixon Administration both wanted the same thing, the means to that goal involved radically different methods. Nixon and Ford wanted a strong defense, but they also wanted to avoid wiping out humanity because of some regional conflict escalating because both superpowers have enough nuclear warheads to re-create the end credits of Dr. Strangelove and no horse sense to stop it from happening. The road to warming relations between the two superpowers involved numerous handshakes with dictators and other human rights abusing monsters.

L: Augusto Pinochet, human rights violating monster, dictator, psychopath; R: Henry Kissinger, Nobel Peace Prize winner.

L: Augusto Pinochet, human rights violating monster, dictator, psychopath; R: Henry Kissinger, Nobel Peace Prize winner.

This necessary dictatorship-coddling is something neither the Right nor the Left understood. Kissinger tried to achieve something unheard of in American foreign policy history: the institution of a foreign policy based on the concept of the balance of power. Again, to quote Eric Alterman’s When President’s Lie:

The country’s history until then [meaning, the Second World War] involved a counterproductive swing between viewing foreign policy as akin to commercially profitable missionary work and the equally implausible desire simply to withdraw from world affairs whenever the natives failed the appreciate America’s plans to improve them.

The balance of power alludes to the disappointing fact that the United States, a global military, economic, and cultural superpower, has operational limitations. In Years of Renewal, Kissinger is forced to handle numerous diplomatic crises with an eviscerated intelligence community; a hostile Congress, public, and media; and the tragic foreknowledge that, because of Watergate’s omnipresent taint, Ford will not be re-elected.

The Rabat Decision and the rise of American neoconservatism become key factors in détente’s decline. The foreign policy apparatus becomes a target for Congressional attacks and the rhetoric of the Right involves the accusation that the Ford Administration is “soft on Communism.” The self-righteous bellows from the ideologically pure clashed with the necessities of running the Department of State and the Foreign Service Corps.

The events in the Middle East mirrored the events in recent years, the culmination of which was the Arab Spring that began in December 2010. Kissinger attempted to bring order and stability to the Middle East in the aftermath of the Six Day War. Today, the United States government is trying to make heads or tails of the still ongoing revolutions, protests, and social unrest covering the Middle East. In both cases, the government was reactive to the crisis. The Arab Spring was a populist uprising against the despots coddled by détente-era Washington, useful pawns ruling petro-tyrannies organized as a geopolitical bulwark against Soviet expansionism. How the United States will answer the developments of the Arab Spring is hard to discern. It’s simply too early to tell. Most of the region remains a question mark, as the future is unwritten, unless one subscribes to the apocalyptic fictions of Tim LaHaye and Jerry P. Jenkins, hackmasters behind the anti-Semitic bestselling Left Behind series. (Just read the plot summary of Glorious Appearing and tell me the series isn’t the Protocols of the Elder of Zion rewritten as a Dispensationalist fantasy.)

Mr. Kissinger Goes to Africa

At least the South Africans aren’t Commies!

At least the South Africans aren’t Commies!

[C]oming to Rhodesia from South Africa is like moving from Wagnerian tragedy to paperback thriller.

“War, Peace, and Allegory in Rhodesia” (1977), Jan Morris

Under Ford, Kissinger finally travels to sub-Saharan Africa. In his continental tour, the most notable visits were to the countries surrounding Angola and the apartheid states of Rhodesia and South Africa. Sub-Saharan Africa represented another facet of the United States commitment to combat the spread of global Communism.

With Angola, a former Portuguese colony, a domestic civil war took on global political dimensions. The situation proved to become chaotic with three different patrons (the United States, the Soviet Union, and Cuba) and numerous neighboring nations harboring anti-government guerrilla groups. The situation was confusing at best, since it is easy to get lost amidst tricky alliances, countless players, and many acronyms. Kissinger asserts the need for intervention, especially in light of the Soviet Union’s lack of influence in the Middle East. The predominantly non-aligned African nations would become potential puppet states to an emboldened Soviet expansionist policy. Cuba’s participation adds another fold to the already delicate situation, since a Cuban Communist victory would be yet another trophy for Castro to wave in the face of the US intelligence community.

South Africa and Rhodesia represent the redheaded stepchildren for American foreign policy. Kissinger finds South Africa’s apartheid morally distasteful, politically counterproductive, and a public relations embarrassment. The mineral rich country of South Africa was the African equivalent of Saudi Arabia: a nation located in a pivotal location for trade run by a hyper-wealthy claque of theocratic bastards. (The Sa’ud Family running Saudi Arabia like their own personal possession and South Africa run in a quasi-dictatorship by the Afrikaner-dominated National Party. South Africa had a democracy with an executive, judiciary, and legislative branches, but all power resided in the hands of the white minority, itself split between the descendents of the Dutch and English colonials. When it became demographically possible, the Dutch regained political control from the English, declared independence from the Commonwealth, and instituted the barbarities of apartheid, the system Jan Morris aptly characterizes as “part mysticism, part economics, part confidence trick.”) In both South Africa and Saudi Arabia, mineral wealth, pivotal location for world trade, and staunchly anti-Communist political ideologies made them useful allies, although both nations have embarrassing human rights records. Then again, Kissinger sees the left’s focus on human rights as a “fetish.”

Rhodesia is South Africa’s counterpart, albeit the farce to the latter’s tragedy. Unilaterally withdrawing from the British Commonwealth in 1962, the Prime Minister Ian Smith instituted an apartheid system, only with a much tinier white population. White rule in Rhodesia seems as foredoomed as Ford’s chances at re-election.

The challenge for Kissinger was to aid South Africa and Rhodesia along into multiracial democratic states without falling to Communism. While organizations like the African National Congress were undoubtedly leftist, if not openly communist, the premise that Communism will spread to South Africa is pretty weak. The Soviet Union had military strength, but seeing South Africa as potential Soviet satellite state borders on the absurd. History has shown that the Soviet Union concerned itself with its European satellite states and its Central Asian republics. The limited Soviet range existed because the Soviet Union possessed a vast geography, small population, and limited economic means. The talk of South Africa or a Central American republic becoming a bastion of Communist aggression sounds like the ravings of a lunatic in a tinfoil hat. Robert Littell put it best with his magisterial spy epic, The Company, when he compared the Soviet Union in the Eighties to “Upper Volta with missiles.”

In the end, Kissinger’s ideals are in the right place, but he is hamstrung by his own amoral balance of power foreign policy.

Evo-Devo of the Right: Conservatives, Neoconservatives, and Tea Party Conservatives

Cut off from the mother country, they remained unaffected by the rationalistic heritage of the Enlightenment or by the democratic dispensation of the French Revolution.

Henry Kissinger on South Africa

On the domestic front, we see Kissinger’s foreign policy assailed on two separate fronts. The McGovernite peaceniks of the New Left and the self-righteous ideologues of the New Right. The mid-Seventies see the birth of the neoconservative movement, a political movement that inherited the passionate rhetoric of the Sixties protests and channeled them into a scathing critique of détente. Without the benefit of public service, the young upstarts accused the Ford Administration of being “soft on Communism.” They were technically correct, but tone deaf to the concept of the balance of power. In Years of Renewal, we meet some rising stars of neoconservatism, many whose names should sound familiar, including Richard Perle and Dick Cheney, then Ford’s Secretary of Defense. To these political fanatics, détente was tantamount to treason, since negotiating with Communist powers was morally anathema. In this way, they are similar to the New Left, although the New Left concerned itself with human rights and anti-nuclear crusades. In both cases, a self-righteous morality could not comprehend the complex realities involved in operating the State Department. The world would be a much better place if all nations were representative participatory democracies with free markets and a robust investment environment. The problem is it’s just not possible. The United States, especially after the disaster of the Vietnam War, wasn’t in the mood to bankroll any more military adventures to topple despots. The problem was this has led to a revival of American isolationism in both wings of the American political system.

The abrupt swings from the zealous missionary desire to convert the world into democracy loving capitalists and the equally strong desire to hole up in our geographically protected shell when those measures fail simply fail to work anymore. Terrorism is a global problem. The free market, despite the halleluiahs from lovers of Ron Paul and Ayn Rand, is riddled with inherent weaknesses that require prudent government regulation. Communism fell in the 1990s and the Great Recession has proven that capitalism is the last man, just not standing, at least not with any superior confidence.

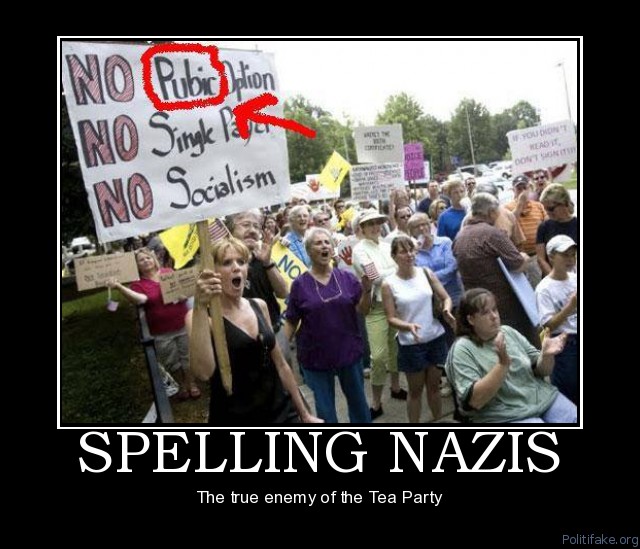

While neoconservatives undermined the Ford Administration, dooming his chances for a second term, the latest variation of conservative ideology, Tea Party conservatism, comes off as a misnomer. The movement began as a grassroots reaction against Big Government and the specter of Socialism, it has mutated into a racist, nativist, anti-intellectual, anti-government party that espouses a ridiculous theocratic anarcho-capitalism. This socioeconomic ideology has one minor flaw: it makes no damn sense! But that’s a rant for another time, suffice to say economic de-regulation cannot coexist with cultural hyper-regulation, at least not for long. Within the United States we have a multicultural participatory democracy whose citizenry is composed of more than the straight white heterosexual conservative evangelicals who think they speak for the whole nation but whose knowledge of the Constitution and the Bible remain, shall we say, a tad on the slender side. Hate to break it those of the self-anointed Elect, but the United States is a nation of laws based on the Constitution, not those of Moses or the Holy See. Ironically, those politicians bolstered by the support of the Tea Party embody this Biblical quote rather accurately: “All this power will I give thee, and the glory of them: for that is delivered unto me; and to whomsoever I will I give it. If thou therefore wilt worship me, all shall be thine.” (Luke 4: 6-7) Now who said that? Jesus Christ or Satan?

Final Thoughts

Are we having fun yet?

Zippy the Pinhead

Reading 5000 pages of Kissinger’s memoirs has been a multiyear project of endurance, frustration, and illumination. While I personally disagree with Kissinger’s political ideology, I can’t help but respect the intelligence, passion, and skill he brought to the positions of National Security Advisor and Secretary of State, and his “balance of power” foreign policy makes a lot of sense, at least in the abstract. But this admiration goes hand in hand with a vengeful hatred and commitment that Kissinger should stand trial for war crimes, specifically those involving Cambodia, Laos, and Chile. (Although making a stink about this is useless unless he has specific charges filed against him, preferably by the World Court or the United Nations.)

While the hatred and admiration commingle into a curdled froth, one has to perform the duty of book reviewer with a careful unbiased eye. Draining an assessment of Republican foreign policy without any personal or political bias would be an exercise in futility (and boredom). The other realization is that Kissinger’s role, while influential and powerful, did not make him the Global Puppetmaster of every atrocity from 1968 to 1976. One has to be careful of anti-Kissinger critiques devolving into thinly veiled anti-Semitic blather. Remember how our government actually works: Kissinger, as Secretary of State and National Security Advisor, acted in the name of the President and in the interests of the United States. One sees in the lunatic scribbling of the extremists Left and Right, turning Kissinger into a latter-day caricature of the All-powerful Conspiring Jew. This is not only inaccurate, but it misses the point. The United States proceeds towards multicultural enlightenment at a glacial pace, battered by the pendulum swings of ethnocentrism and moral relativism. Because Kissinger was from a Jewish family living in Germany, fled to the United States, worked in Army Intelligence, and later enjoyed a successful academic career, all these facets provide targets for anti-intellectual attacks. His intellect, Ivy League status, and foreignness deflect the justified and necessary questioning of his actions on behalf of the US government. Luckily, everyone from the National Security Archive to the late Christopher Hitchens have worked tirelessly to pry documents from the NSA, CIA, and other agencies to shine a light on Kissinger’s misdeeds.

Even after trudging through 5000 pages of whitewash, I realize that the balance of power foreign power philosophy makes sense. The United States has limited capabilities, especially in terms of nation-building. Our culture is too infatuated with military technology and power to understand that we have to fix the apple cart after he kicked it over and given the vendor a televised show trial. The United States needs to understand the limits of its capabilities in geopolitical terms. Once these limits are understood and accepted, then one can go about pressing palms and organizing alliances. The forward thinking helped Kissinger open China. This foreign policy coup would be similar to President Obama “opening” Iran. Since the Arab Spring is still a work in progress, one needs to facilitate other options, because the tide may strike the shores of Saudi Arabia with Arab youth unhappy with being thought of as Sa’ud Family property.

The world’s future is unwritten, but Kissinger’s memoirs provide a fascinating document of the inner workings of American foreign policy and the global political personalities that shaped the paranoid Seventies.

And now for some singing …

![henrrry_7[1]](https://driftlessareareview.com/wp-content/uploads/2012/06/henrrry_71.jpg?w=720)

Earlier guesses at the identity of ”Z” included Zbigniew Brzezinski and Henry Kissinger, the foreign policy gurus of previous administrations; Robert Gates, the former No. 2 CIA chief who works at the White House; and retired Lt. Gen. William Odom, former head of the supersecret National Security Agency.

LikeLike