A game of tennis with a good friend signifies that Alan Ripley has achieved “the good life.” It is 1988 and Alan works as a Boston area real estate lawyer, has a loving wife working in academia, and a growing son. The idealistic picture of late twentieth century domestic bliss fractures when Rory Dekker enters Alan’s life. Alan met Rory twenty years ago as the intense fires of Sixties idealism curdled into resignation and rage. With Nixon ascendant, Alan and his friends decide to “make a difference.”

A game of tennis with a good friend signifies that Alan Ripley has achieved “the good life.” It is 1988 and Alan works as a Boston area real estate lawyer, has a loving wife working in academia, and a growing son. The idealistic picture of late twentieth century domestic bliss fractures when Rory Dekker enters Alan’s life. Alan met Rory twenty years ago as the intense fires of Sixties idealism curdled into resignation and rage. With Nixon ascendant, Alan and his friends decide to “make a difference.”

Inspired by a seductive ideologue named Lily Culp and aided by a couple ex-cons, the tiny cadre of revolutionaries decide to participate in a heist. The heist involved raiding a gun store, stealing the weapons, and distributing them to blacks. It all seemed to make sense, at least on paper. Then the day Alan should have participated in this nascent revolutionary action, he becomes sick and has to bow out. The Lyletown Six became the Lyletown Five. In the resulting melee, one person died, the others fled, and Rory ended up serving hard time. Now Rory has returned into Alan’s life and Alan doesn’t know why. Blackmail? Revenge? The reunion of friends possesses an ominous tinge.

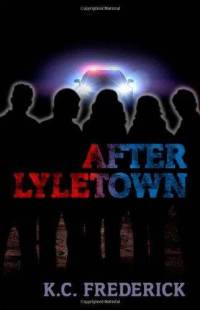

After Lyletown by K.C. Frederick is a meticulously constructed narrative that Alan and Rory dealing with the consequences from the events of the Sixties. On the surface, the premise is reminiscent of a thriller. The novel itself operates on a much smaller, much more psychological level. It is a novel of interiors. Much is given over to Alan thinking and rethinking his decisions in the past and calculating the degree of his culpability. The superficial portrait of the upper middle class real estate lawyer is only part of the picture. Between the fires of Sixties idealism and thriving in Reagan’s America, Alan suffered one failed marriage and a dead-ended literary career. He then reinvented himself as a law student, divorced his first wife Martha, and remarrying an attractive literary scholar named Julia.

Because of Rory’s silence in prison, Alan thinks he owes the ex-con something. This is exacerbated by Alan’s realization that he could have lost everything if Rory chose to expose Alan’s part in the botched heist. To further complicate matters, Alan chose to not reveal this part of his life to Julia.

What follows is a series of meetings between Alan and Rory. Alan mired in self-guilt, Rory noticeably vague on his current situation. Rory says he needs money, but doesn’t elaborate. Alan, with lawyerly rationalizations, decides best not to ask, since too much knowledge would make him more culpable, especially if Rory’s plans for the money aren’t exactly legal.

Some passages in the novel seem a bit too on-point, like when Alan visits an elderly Polish woman who is his client in an eviction case. The woman worked for the Polish resistance and lives on a modest pension. The woman’s work in the resistance seems like an obvious mirror to Alan’s work with the Lyletown Five. On the other hand, Julia’s father fought in the Second World War but refused to talk about it. The war left him taciturn and tortured on a deep psychological level. The omnipresence of war creates these peculiar ripple effects. Since the story is set in the Late 80s/Early 90s, the reader could project the future for Tommy and how the future War on Terror will effect him.

The novel is an exploration of how war, prison, and affluence effect individuals, told at an unhurried pace. The writing shimmers with descriptions of Innisfree, the Vermont cabin Julia’s father built, and Boston bars (dive bars and trendy Yuppie havens alike). Not a narrative of spectacular confrontations but one that builds menace with a slow intensity and allows for the exploration of human interrelationships damaged by bad personal and foreign policy decisions.

Excellent review!

LikeLike