I: The Mount Everest of Modernism

“It is not the mountain we conquer, but ourselves.” – Sir Edmund Hillary

The Cantos. Ezra Pound. The very mention of those names send shudders down even the most well-read literary snob. T. S. Eliot’s “The Waste Land” seems like a small indentation in comparison. The only work with comparable difficulty and lit crit caché is Finnegans Wake by James Joyce. Reading these works carries along serious bragging rights. “I saw the new Terrance and Philip movie. Now who wants to touch me?” Eric Cartman said in the South Park movie.

As a reader and enthusiast of literature – like the term culture, a loaded term with classist, racist, and ethnocentric connotations – I enjoy reading works that challenge me. I’ve read In Search of Lost Time (all seven volumes), Ulysses, and Lolita. However, I’m not a comparative literature major and I know one language really well – English (Midwestern style, middle class suburban variation), but I love language and languages. Of those challenging books, I read all in their annotated forms. The critical apparatus, whether a citation, glossary, or explanation, usually proved invaluable to the understanding of the work.

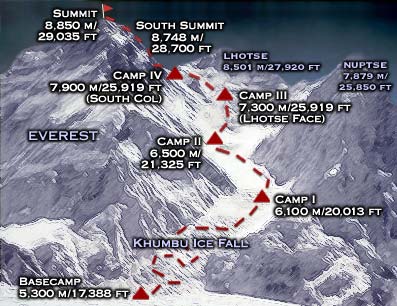

Why read the Cantos? Why climb Everest? Because it is there. What did Old Ez have to say, really? Is there value in the epic poem written by a polymath accused of treason and found insane? Can’t be any worse than struggling through the sub-literate scribbling of Dan Brown, Stephanie Meyer, and Kevin J. Anderson.

I’ve completed the Cantos. I could only make it through Chapter 1 of Angels and Demons. Draw your own conclusions.

This review is not your normal review. The poem doesn’t lend itself to our culture of spoilers. I will focus on the poem as an epic, the multitude of voices involved, treason, and economics.

II: The Epic Form

“Nel mezzo del cammin di nostra vita

Mi ritrovai per una selva oscura,

Che la diritta via era smarrita.”

“In the middle of the journey of our life I came to myself within a dark wood where the straight way was lost.”

The Divine Comedy, Part I: The Inferno. First lines, Dante Alighieri

The epic poem has long fallen out of fashion, let alone read or spoken. Pound’s work encompasses entire cultures, eras, and languages. It is a work of poetry, an economic treatise, a defense of Italian fascist politics, and a commentary on Modern Culture. The only way Pound could get all his ideas down was to enumerate them in a “poem of some length.” And it is long. There’s truth in advertising when considering the Cantos as an epic. The New Directions hardcover runs a brisk 824 pages.

While reading the Cantos, one should keep the idea of epic poetry in her mind. Canto I recalls the voyage of Odysseus and the entire work has structural parallels with Dante’s Divine Comedy. Scholars have traced sections in the Cantos paralleling “Hell,” “Purgatory,” and “Heaven.”

Pound realized that the epic form was the only viable means of fulfilling his artistic project. As a “poem to include history,” it was also “a tale of the tribe.” He began his project with A Draft for XXX Cantos, published in 1930, although the earliest cantos had been published in different forms and orders as early as 1924 (A Draft of XVI Cantos). There are also the three Ur-Cantos included in Personae (1926), an early collection of his poetry. The last canto, called simply Fragment, was published in 1966. The project would literally encompass his entire life, from the earliest incarnations – sharp Modernist jabs at the decadent and decaying fin de siècle poetry of Swinburne and other Victorian hothouse flowers – to the very end, with Allen Ginsberg’s career ascendant. (One should note the similar fate of Victor Hugo’s epic novel, Les Misérables, heavy on Romanticism, even though it came out in 1862, when Romanticism was being superseded by Naturalism and Realism.)

As Dante had his Vergil, I found aid with A Companion to The Cantos of EZRA POUND by Carroll F. Terrell. I would not have even attempted this without this book. It is indispensible. With 10,421 glosses and many other aids (translations, exegeses, and an updated bibliography), it “set[s] out lucidly and with brevity in a format designed to aid the moment of reading rather than aeon of research” (Jed Rasula’s review on the back cover).

Like the Divine Comedy, the Cantos embrace both the epic and the personal. Besides being a work with epic scope, it is also Pound’s personal exploration of political, economic, and aesthetic issues. He brought together things that concerned him on a personal level and included material taken from his personal library. In the same way, my reading experience involved my personal journey with Pound through the Cantos. Some cantos seemed merely academic exercises, while others I found deeply effecting, especially the Usura Canto (Canto LXV). Like Pound, by the end of the work, I felt exhausted.

III. Voices, Sources, Pastiche

“Beware of thinkers whose minds function only when they are fueled by a quotation.” – Emile Cioran, Anathemas and Admirations

A major trope of the Cantos is Pound’s use of different voices. It is a technique he adopted early. His early collection of poetry was Personae, named after the masks used in Greek theater. In his translations, he usually adopts a freewheeling style, translating in the spirit of the original, not a literal translation of said work. This was a radical departure in the common practice of translation, although Victorians and Edwardian translators would purposely mistranslate anything too saucy or scandalous. A handy practice when it came to controlling the minds and souls of young boys in the English public school system forced to translate Greek and Latin poetry. (Something one should keep in mind when you’re looking for an accurate translation of Catullus or Aristophanes. The dirty versions are probably more accurate.)

In the Cantos, Pound adopts many different voices, including Provençal troubadours, Chinese and Neoplatonic philosophers, Dante, Ovid, and Odysseus. In Canto I, he begins with a retelling of Odysseus visiting the Underworld and ends with a commentary on the translation of the Odyssey.

Besides adopting voices, he uses the technique of pastiche and collage to bring about multiple associations. In the early cantos, it is a jagged back-and-forth between Classical and Renaissance settings and modern times. Then he brings in Chinese characters and makes the poem not only a textual experience, but a visual experience. When I read Thrones, it reminded me of the typographical exuberance of House of Leaves.

KUNG (Confucius)

KUNG (Confucius)

The adoption of different voices and the use of pastiche were part of Pound’s attempts to forge a new philosophy. In his words, create a space “between KUNG and ELEUSIS” (Canto LII).

ELEUSIS

ELEUSIS

IV: Jefferson and/or Mussolini

“You’re the top.

You’re the Great Houdini.

You’re the top.

You are Mussolini.” – Cole Porter, “You’re the Top” (1934)“He chose poorly.” – Grail Knight, Indiana Jones and the Temple of Doom (1989)

In the words of Talleyrand, “Treason is a matter of dates.” Pound, a longtime American expatriate, has the black stain of treason upon his literary legacy. While he remains a poetic genius and guiding light behind several major Modernist movements (Imagism, Vorticism), one must contend with the dirty world of politics as well as the idealistic world of art.

But it is unfair the slap the label traitor upon Pound without some historical context. This isn’t to excuse his actions (and he did commit active treason), but to explain them in an attempt to understand them. In the 1929, the Stock Market crash was part of the global economic catastrophe known as the Great Depression. Two major results occurred: free market capitalism lost its credibility and, in turn, representative democracy. If one lost faith in democracy and did not dare go Communist, the alternative path was the new political phenomenon called fascism. (If you are interested in fascism, I would recommend reading A History of Fascism: 1914 – 1945 by Stanley Payne and Nazi Literature in the Americas by Roberto Bolaño.)

But Pound also admired the Founding Fathers, especially John Adams. A major sequence of cantos involves the Jefferson-Adams correspondence.

Pound’s involvement with Italian fascism is unfortunate, especially when he sided with Mussolini in World War II, going so far as to compose a canto regaling the reader about how an Italian peasant child led Canadian troops through a minefield. But his treason and acceptance of fascism should also make us look at ourselves. Are we so much more righteous and virtuous than Pound? What does treason mean today? When former President George W. Bush used kid gloves with Saudi despots and other pro-U.S. dictators, the word treason is rendered meaningless. Jeanne Kirkpatrick rendered Pound’s treason into the high art of diplomatic discourse. So Pound sided with an anti-democratic dictator. If, according to Kirkpatrick, Mussolini sided with the United States, then we are fine with that? Remember, in World War II, our greatest ally was STALIN! While we owe the Greatest Generation our thanks and gratitude for their selfless sacrifice, the global conflict was not a simple division of Good and Evil like one finds in Tolkien’s Lord of the Rings.

Treason is a matter of perspective. The President and a member of al-Qaeda fandom.

Treason is a matter of perspective. The President and a member of al-Qaeda fandom.

Mussolini, Hitler, and Hirohito performed acts of insidious evil and left death and destruction in their wake. But the United States had racial segregation, restrictive covenants against blacks and Jews, and the whole Native American thing. Great Britain and France had colonial empires leaching out resources and oppressive native non-white populations. And Stalin did what Stalin did best: kept the trains running on time and the Gulags full.

Keeping one hands clean during a conflict that immense is downright impossible, but it puts things in perspective when the word “traitor” is hurled around. It is Pound’s version of the Scarlet Letter. One can not dismiss the charges of treason, one must examine the charge and use the opportunity to plunge into the black muck of the human soul.

V: Usury and Economics

“Economics? Monetary theory? You some kinda big city elitist? I done gone preparified for the Rapture. The world is 6000 years old and Jesus is gonna return to get rid of all them gays, liberals, and Jews. Sarah Palin’s purty!”

“Economics? Monetary theory? You some kinda big city elitist? I done gone preparified for the Rapture. The world is 6000 years old and Jesus is gonna return to get rid of all them gays, liberals, and Jews. Sarah Palin’s purty!”

“All the perplexities, confusions, and distresses in America arise, not from defects in their constitution or confederation, nor from want of honor or virtue, as much from downright ignorance of the nature of coin, credit, and circulation.” — John Adams, letter to Thomas Jefferson, 25 August 1787

Anyone sending money to a credit card or paying a mortgage understands the term usury. Pound should be commended for attempting to involve economics in his epic. He should be smacked for being such an anti-Semitic bastard. Yes, anti-Semitism was a common practice at the time, but he wrote the Cantos well into the 1960s and anti-Semitism gradually became part of the great collection of disreputable and stupid ideas, along with the Flat-Earth Theory and Biblical Creationism. To be fair, the Catholic Church dropped the charges of deicide against the Jews in 1965.

Economics is a cold, boring, dismal science. Pound embraced a little known economic movement known as Social Credit. The movement’s premise advocated local currency based on local resources. It also opposed “interest.” When you pay 15% interest to your credit card provider, do you ever ask why? Why this specific rate?

The world has recently experienced a credit crisis, a housing crisis, and an economic recession in short order. It is easy to blame the politicians and bankers, since they are easy targets. But blame also rests with the people. Caveat emptor. Buyer beware. If it is one thing Americans fall victim to with alarming consistency, it is their own ignorance on matters of money. (Read the John Adams quote again.) Again and again, we believe the bubble will last forever and we will never be poor again. It is the economic equivalent of the blonde heroine in the horror movie opening the door to the basement. “No! Don’t go in there!”

Pound thought the economic solution was Social Credit. The flush times of the Fifties and Sixties did away with the idea of Social Credit, giving the movement crackpot status. But Social Credit’s advocacy of local currency and local resources seem similar to our attitudes toward food. Locavore has become a new word in the Oxford English Dictionary. We are concerned where our food comes from, the use of pesticides, and how it tastes. “Local” now carries the connotations like “good” and “healthy” and “putting money into the local economy.” Why not think the same way about money?

For the last quarter century, the United States has seen jobs and wars as our major exports. In our mad rush towards material wealth, companies have valued the bottom line more than job security. Car companies and computer companies are the more well-known examples. Why not try to grow the companies within the United States? Right now we have a recession, high unemployment, and we buy cheap crap from China. Does not make a whole lot of sense. For lesser prices, we can afford lesser-quality products. Instead, why not bring back these jobs, create better products, and pump money back into the United States? One can stretch the idea of “local” in Social Credit to “within the United States.”

Paying high interest rates – not only to credit card companies but to predatory lenders that blight urban areas like plague – is non-productive. Money that pays that interest could have been used to purchase something else. Interest rates (and student loans) are the new indentured servitude. But within our current culture, since it was your choice whether or not to purchase that thing (or your education), it is your fault you have to pay and you are a lesser being for that. As opposed to advocating that the State bankroll free higher education to its citizens, thus insuring more productive citizens who will put more money into the economy. What is more productive? Is it a debt-free student graduating college and entering the work force, or paying student loans for decade upon decade?

In our mad quest for short-term satisfaction, we have lost sight of our long-term goals.

VI: A History in Fragments, or To Fail Better

Germany, 1945.

“Ever tried. Ever failed. No matter. Try again. Fail again. Fail better.” – Worstward Ho (1983), Samuel Beckett

Pound never succeeded in finishing his epic poem. By the late 1950s, he embarked on the Paradise sections. One of the rare pleasures of reading the Cantos is how Pound recapitulates the themes and ideas. It also reveals a structural integrity true to the project of the epic poem. The last section is entitled “Drafts and Fragments.” In short cantos, some no longer than a couple pages, he continues to explore the issues and take on different personae.

“Drafts and Fragments” mirrors both his mental state and the global post-war experience. Following his incarceration, Pound spent time in an insane asylum. Europe, shattered by two world wars within a century, had to rebuild. Pound’s experiences and loss of control also reflect the innovations and insanity of Dave Sim, creator of the epic 300 issue comic Cerebus. Like Pound, he began the epic as a parody of earlier forms and became a major innovator of his medium. Unfortunately, Sim, like Pound, became a crank and a crackpot, his work disintegrating in the process.

But Pound’s failure is also his triumph. By the end of the Cantos, we again read incredibly moving poetry, short and soaked with heartache and regret. After slogging through 800 pages of allusive, elusive, dense, forbidding poetry, the fragmentary cantos feel like fresh air and clear skies.

Whoo-hoo! Gutsy move, Karl, tackling Pound and managing to sound like you know what the hell you’re talking about. I have a couple of books by Pound and they, invariably, are the ones that snicker at me in contempt each time I pass my bookshelves. They know I’m not bright enough to comprehend even a small portion of what they contain. You mix opinion and analysis with your usual invective and satirical swats at every sacred cow grazing in the dumb paddock.

Hats off to you, kid, and keep up the fine work…

LikeLike

this post gave me reason to think, thanks…

LikeLike